In 2016, in a speech commemorating anti-racist activist Steve Biko in South Africa, communist essayist and feminist Angela Davis mentioned the many struggles of our time, including the “sentient beings who endure pain and torture when they are turned into food.” Four years earlier she had argued that animal rights were “one of the components of the revolutionary perspective.” Surprising as this connection may sound, it actually goes back a long way – eco-feminist writer Pattrice Jones once said: “The animal liberation movement is a feminist movement1.” What could explain this historical association?2

* *

*

Available data suggests that 68 to 80% of animal rights activists are women3. Considering its specific demographics, the animal rights movement may even be one of the largest women’s movements second only to the feminist movement itself. Women tend to be more concerned about how our communities treat animals: they consume less meat than men and are more likely to renounce scientific careers involving violence towards animals. Nowadays, practices and institutions centered around violence and the killing of animals are still dominated by men (animal farming, hunting, fishing, trapping, slaughter, butchery, animal research, rodeos, bullfighting, etc.). Writer Virginia Woolf noted as early as 1938, in Three Guineas, that “the vast majority of birds and beasts have been killed by you, not by us4”. Conversely, women outnumber men when it comes to caring for and helping animals – mostly unpaid activities, such as distributing food to stray animals, creating shelters and sanctuaries, participating in public education campaigns, founding animal rights organizations, opposing animal research and hunting, etc.

Women’s concern for the plight of animals in our communities has been so constant that it is difficult to tell the story of the animal rights movement without also telling the story of women. The suffragettes’ movement against vivisection and the famous Brown Dog Affair immediately come to mind, but the story started much earlier. Back in the 17th century, Margaret Cavendish, the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society of London, spoke out against philosophers Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes’ ideology of human exceptionalism and human supremacy. In France, Marie Huot, Louise Michel, Séverine, Sophie Zaïkowska, and other feminists involved in socialist and anarchist struggles, raised their voices for animals. Though feminist studies have overlooked how important animal rights issues are in feminist writings, one cannot tell the history of women without mentioning the animal rights movement. This is, in essence, the subject of Carol J. Adams’ now classic book, The Sexual Politics of Meat – A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory5.

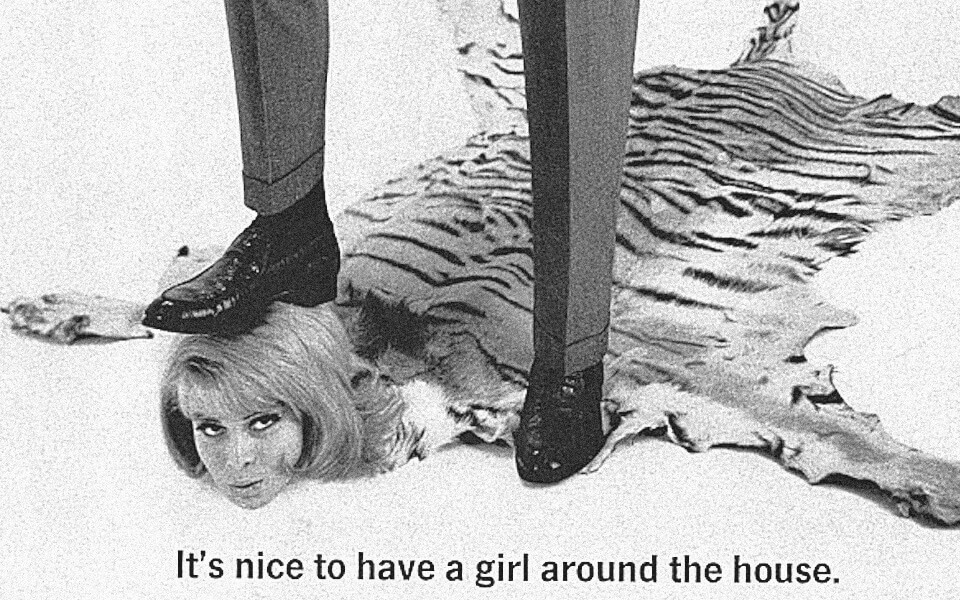

Advertising for Mr Leggs pants.

Vegetarianism: an unspoken aspect of feminism

Adams’ Sexual Politics of Meat is not a treatise on moral philosophy or animal ethics; it is primarily a criticism of feminists who have ignored the “vegetarian word” of their predecessors. Adams criticizes feminist studies for not having paid enough attention to the breadcrumb trail that runs through the material in this corpus: several authoresses express, be it directly or through their characters, their concern for the fate our communities hold for animals. They oppose the imprisonment and killing of animals for food we do not need, and they frequently link the oppression of animals with that of their own. The major reason why women and animals share this historical and material proximity is because they have a foe in common – patriarchy, which chains them to a specific role in the world order. Inextricably linked to human supremacism, patriarchy ranks individuals based on a hierarchy of values that places the able-bodied, able-minded, self-controlled, adult, white, male human at the very top of the pyramid of beings.

By appealing to a number of biological characteristics – such as sex or species – supposed to reflect the specific ‘nature’ of an individual, these supremacist ideologies attempt to justify the unequal treatment and uneven consideration of individual interests. Femininity and animality are perceived as determining properties for women and animals, properties that do not quite fit the dominant model. While men are associated with rationality, culture, emotional control, and the domination of nature, women are associated with the body, emotions, intuition or instincts (irrationality), passivity, and therefore considered closer to animals and nature than men. Women and animals would thus be “naturally” relegated to the background and considered second-class beings. United Statesian philosopher Lori Gruen argues that a community of fate and solidarity between women, indigenous peoples, racialized groups, and non-human animals6 results from the common history of patriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism, and human supremacy.

Ideologically, traditional justifications for oppressing specific human groups are often based on the idea that human domination over non-human animals is naturally just. This idea is explicitly found in several classical texts of Western thought. Aristotle wrote:

“Now if nature makes nothing incomplete, and nothing in vain, the inference must be that she has made all animals for the sake of man. And so, in one point of view, the art of war is a natural art of acquisition, for the art of acquisition includes hunting, an art which we ought to practice against wild beasts, and against men who, though intended by nature to be governed, will not submit; for war of such a kind is naturally just.7”

In his view, the domination of some humans by others (the supremacy of “rational” and “civilized” beings over “barbaric” human beings, “intended by nature to be governed”) is justified because it is the natural extension of the naturally just domination of rational animals over animals with no logos8. Not only would it be just for inferior beings (women, slaves, animals, children) to obey superior beings (male owners/citizens) and serve their interests, it would also be mutually beneficial:

“For tame animals have a better nature than wild, and all tame animals are better off when they are ruled by man; for then they are preserved. Again, the male is by nature superior, and the female inferior; and the one rules, and the other is ruled; this principle, of necessity, extends to all mankind. Where then there is such a difference as that between soul and body, or between men and animals (…) the lower sort are by nature slaves, and it is better for them as for all inferiors that they should be under the rule of a master.9”

Just as patriarchy purports that women’s subordination is for their own benefit, there is the idea that a “natural contract” or a “domestic contract” has been established between humans and domesticated animals who “offer” their bodies to us and “give” us access to their reproductive services (their children, their maternal milk, their eggs) in exchange for our care and protection. In fact, it is not uncommon for figures of femininity and animality to be combined in our daily representations: the Tumblr blog “Je suis une pub spéciste” (I’m a speciesist ad)10, for example, reveals the omnipresence of “carno-sexism” in popular culture. Most notably, in advertising, not only are women animalized (depicted alongside cuts of meat or literally shown as pieces of meat), animals intended for consumption are feminized and therefore sexualized (chickens in high heels, turkeys in bikinis, pigs with lipstick, etc.). The accompanying slogans often lack subtlety: we like them “juicy”, “wild”, “plump”, etc. These anthropomorphized (or rather feminized) animals are depicted as consenting victims who just want to be consumed. Like women in patriarchal societies, they are represented as servants to men and literally just bodies, with no regard for their individual psychological lives.

Adams argues that animals are “absent referents” who disappear as individuals (a pig, a cow) to become objects (pork, beef, legs, breasts, etc.). Representing animals and women as (pieces of) bodies devoid of subjectivity reinforces the idea that they have only an instrumental rather than an intrinsic value. They are considered solely in terms of how useful they are to men (“men” meaning both humans and males). Women and animals are commodified, instrumentalized, appropriated, and deprived of self-determination. Their common condition therefore results from their being dominated. Feminists have offered three typical responses to this association with animals. Some have rejected their association with the body, emotions, animals, and ‘nature’, claiming to fully belong to the dominant group, the male realm, rationality, etc. Others have opposed the idea that the “masculinization of women” is the path to emancipation (Vandana Shiva) and instead have attempted to reverse the hierarchy of values by revaluing those activities perceived as distinctively feminine (caring, worrying and tending to others, catering for their needs, etc.) and, conversely, devaluing the sphere of masculine values. Beyond these two approaches associated with liberal feminism and cultural or radical feminism, others have sought a third way: attacking the logic of domination itself and its underlying dualisms.

“We are not animals!”

Like animals, women have been symbolically and even legally assimilated to property. Because of this past history that enabled their domination, some women have sought to break their shackles by denying this association. At a protest against pornography in New York, United Statesian feminist Andrea Dworkin held a sign that read: “We are not animals!”. Of course, Dworkin was not trying to deny that women are animals. The word “animal” here had nothing to do with biology or science: it referred to a social construction, a label, a stereotype used to cast contempt upon an individual or a group in order to legitimize their subordination and to make it morally acceptable. Feminists who criticize the instrumentalization and appropriation of women often oppose only one aspect of the women/animal comparison: while objecting to the idea that women are treated as “livestock”, they do not oppose the way in which said ‘livestock’ is treated… This implies that the sexual exploitation of human women is morally wrong, unlike that of females of other species, and that inflicting sexual violence on female bodies outside of our biological group in order to appropriate their flesh, their eggs, their maternal milk, and their children, is therefore acceptable. By insisting that we are “all human” and that we are “not animals”, members of subordinated human groups have thus attempted to claim their right to belong to the dominant group, with the associated rights and privileges, without questioning the exploitation of non-human animals, without challenging the very principle of a hierarchy between individuals.

Fighting the logic of domination

Many feminists criticize seeking emancipation at the expense of an even more marginalized group. They oppose the idea that women’s emancipation must – and can – be achieved to the detriment of other subordinate individuals. They especially target feminists who have asserted their willingness to hunt and go to war, or those who didn’t refrain from using vivisection to drive their scientific careers to show that they are not “too sensitive” and can be as violent, ruthless, “rational”, and domineering as men. For feminists like Carol J. Adams, Josephine Donovan, Lori Gruen and Greta Gaard, the goal of feminism is not simply to push women up the governmental or corporate ladders or to give them equal access to labor in the service of capitalism, but to radically transform the way our communities work. Seeking emancipation at the expense of a more vulnerable being is, for one thing, fundamentally unjust (and contrary to feminism understood as a struggle against all forms of oppression). It is also impossible because oppressions feed off each other.

In this regard, many feminists argue that several forms of human oppression (patriarchy, slavery, colonialism, ableism11) are closely linked with the supposedly “naturally just” domination of humans over other animals. The exploitation, domination and oppression of animals enables and encourages violence against humans because it provides the material and ideological conditions for the oppression of members of marginalized and alienated human groups. “Material conditions” include the chains, weapons, whips, and cages used to violate an individual’s freedom and physical integrity or to impose authority and force obedience, as well as the reproduction control techniques applied to animals intended for slaughter or forced labor. These techniques were often developed to enslave animals and then used to enslave other humans (Frederick Douglass, a slave from Southern United States, describes how he was sold at a ‘livestock’ auction alongside pigs, cows and horses12).

The political, economic and legal institutions that legitimize and encourage the subordination, appropriation and exploitation of animals also subordinate human groups, typically considering them as property or commodities or as “legal things” and not “legal persons”. Anti-speciesist feminists therefore reject the idea that an individual can be a “slave by nature”, that there is a metaphysical hierarchy of individuals ruled by “rational and autonomous beings” supposedly imbued with a “natural right” to command “inferior”, “non-rational” individuals, and “beings of nature”, programmed by “biological determinisms”. According to these feminists, every single individual’s life, freedom, autonomy and physical integrity should be respected regardless of their biological or social group, degree of intelligence, cognitive abilities or disabilities, and usefulness to the dominant group. In her famous foreword to Marjorie Spiegel’s The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery, African-American feminist Alice Walker argues that: “The animals of the world exist for their own reasons. They were not made for humans any more than black people were made for white, or women created for men.” Feminists who acknowledge the injustice of speciesism thereby identify a common enemy to be fought: the arbitrary hierarchization of individuals and the idea of a “naturally just” domination. Veganism can then be seen as a form of resistance to patriarchy and human tyranny. In a way, refusing to exploit animals, acknowledging that they experience subjectivity and have interests of their own, amounts to “disobeying” patriarchy, thus affirming one’s own subjectivity, one’s ability to question the world order long since imposed and presented as immutable.

From pathologizing to criminalizing concern for animals

Being attentive to gender within the animal rights movement is essential since the intimate link between women and the animal rights movement may have been detrimental to both causes. On the one hand, in a society where exploiting, oppressing and (not criminally) killing animals is considered completely normal and natural (a business like any other), the fact that women have been associated with the defense of other animals has been another opportunity to represent them as irrational, frivolous, puerile, too emotional to be considered legitimate in political debates. Conversely, in a patriarchal society, concerns associated with women are regarded as secondary if not openly despised and denigrated as “sentimental” and “childish.” Depicting the animal rights movement as a worry for “good old ladies’” has played a part in it not being taken seriously. In other words, in communities supporting both human supremacy and patriarchy, the association between the animal rights movement and the women’s rights movement has been used to discredit both causes.

In fact, targeting the demographics of the anti-vivisection movement was one of the favored strategies of vivisectionists – as if pointing out that a social, moral or political cause is primarily a women’s concern were enough to refute it. Nowhere are attempts to discredit and depoliticize the animal rights movement on both sexist and ableist grounds more obvious than in the medicalization and pathologization of female animal activists. The women’s rights movement is familiar with the accusation of hysteria against women who refused to submit to the authority of men and failed to thrive in their traditional social roles, but it still largely ignores the fact that the medical profession also attempted to diagnose concern for animals as a mental illness that especially affected women. In France, the 1893 Guide pratique des maladies mentales (A Practical Guide to Mental Illness) includes an entry on “zoophilia” (at the time, this word had a more direct etymological meaning: love of animals): “Some people have an exaggerated affection for animals for which they would sacrifice all human beings. Anti-vivisectionists belong to this category of sick people, and their followers are mostly women13.” In the United States, in 1909, journalist Charles Dana invented the notion of “zoophil-psychosis” to stigmatize and discredit anti-vivisectionist activists by portraying them as “insane”14. These attempts to pathologize and medicalize concerns for animals aim to depoliticize the dissidence of female animal rights activists. As Adams argues, feminist studies themselves have contributed to this repression by ignoring the authoresses’ vegetarianism or by equating it with an eating disorder completely unrelated to morality or politics. Depoliticization of the animal rights movement is still obvious in the ways in which veganism is seen as a diet, a “personal choice” or a “lifestyle” rather than a political act of protest against institutions based on animal exploitation, oppression, and slaughter.

Nowadays, animal rights activists are more often called “extremists” or even “terrorists” than “insane” and “neurotic”. In other words, the accusations are getting less medical and more criminal. Anita Krajnc – foundress of the Save Movement in Ontario – was arrested in October 2016 for giving drinking water to pigs in a transport truck on its way to the slaughterhouse. In the United States, animal rights and environmental activists are at the top of domestic terrorist threats. Following the enactment of the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (AETA) in 2006, “ag-gag” laws were passed in several US states to criminalize economic loss to animal businesses, and the production, possession, and distribution of video footage from animal farms and laboratories15. With these laws that explicitly target whistleblowers by hindering the disclosure of what is going on in the animal industry, we have to admit that we live in a world that criminalizes not violence against animals but any attempt to help them and to thwart those who exploit them.

Beyond veganism: helping animals

Beyond being vegan and minimizing their contribution to animal abuse, many feminists involved in animal rights activism consider that it is our duty to actively assist animals and stand against their institutionalized exploitation and killing, even when this involves disobeying the law. They carry out various forms of direct action to help animals, including “open rescues”, which aim to expose the horrific conditions in which animals live and die and to free them to be rehoused and cared for in sanctuaries and refuges. Their goal is not only to raise awareness about the fate of other animals and to show the faces of the animals and the activists who help them, but also to enable the animals to enjoy their lives as they see fit and develop interpersonal and social relationships on their own terms. Sanctuaries for domestic animals intended for slaughter offer a precious opportunity to learn what these animals want and what kind of life, what kind of relationships they would like to have if they had the chance. They also give us a glimpse of what fair and respectful human-animal relationships might look like.

Feminists involved in the animal liberation movement do not necessarily advocate rewilding domesticated animals or letting them go extinct, but developing non-oppressive and non-exploitative relationships with these animals who have been part of our communities for millennia, and are yet treated as an inferior caste. Anti-speciesist feminists do not demand better regulation of the animal trade; they demand its end. Their objective is not to reform the practices and institutions built upon animal exploitation and slaughter, but to abolish them. Animals are not commodities to be bought and sold. They are not property, nor are they “natural resources” that should simply be exploited more sustainably. They are individuals in their own right. They have a mental, emotional and social life, and they should be able to live their lives as they see fit.

Human and animal liberation: solidarity between the feminist and animal rights movements

Feminists should show more solidarity with the animal rights movement, despised for often sexist (and ableist) reasons and currently exposed to fierce political repression. It is not simply about establishing logical links between sexism, speciesism, racism, and ableism (as philosopher Peter Singer does), but actual material, historical and ideological connections, showing how the various forms of oppression feed off or strengthen each other. Attempting to emancipate humans while keeping animals in slavery and reinforcing the idea that they are merely commodities and resources at our disposal is not only unjust, but also impossible, since the allegedly “naturally just” violence against animals provides the template that several forms of human domination have been and still are based on. It is essential to politicize food and stop normalizing the unnecessary slaughter of animals for food, out of respect for both farmed and wild animals.

Since the 1970s, humans have caused vertebrate wildlife populations to drop by more than half (52%)16, mostly through direct exploitation (fishing and hunting) and through the destruction of their habitat largely due to the increase in the number of farmed animals. Dismantling the animal farming industry should be at the heart of current social and environmental struggles, since breeding animals for meat production is one of the main causes of soil depletion, water pollution and wastage, greenhouse gas emissions, disappearance or degradation of wildlife habitats, deforestation, and increased antibiotic resistance17. Not only is it about justice for animals, it is also about food justice and intergenerational justice. Livestock farming already occupies most of the world’s farmland (78%) while providing only 13% of calories and less than 30% of protein worldwide18. Global fisheries – which are so devastating that there will be more plastic than fish in the oceans by 2050 – produce only 6.5% of protein and 1% of calories in the world19. Meat, which is mainly produced for the wealthiest, threatens global food security since farmed animals now compete directly with humans for food and water (95% of the world’s soy is destined to animal farming). Despite the already massive negative impact of the 70 billion birds and mammals fattened and killed each year, the UN foresees a 50-70% increase in global meat production by 2050. In light of this grim prediction, a global transition to a vegan diet is urgent and should be considered our major hope to build a food system that is fairer, more environmentally-friendly and more respectful of the human and non-human animals sharing the planet with us.

Feminism and anti-speciesism should be seen not as two separate struggles but as mutually supportive movements fighting forms of domination bound by a very similar agenda.

Feminists, and more generally progressive activists, cannot turn a blind eye to violence against other animals: failing to address the issue of speciesism amounts to contributing to the very patterns of violence, arbitrariness, and injustice that underpin patriarchy, white supremacy and ableism.

Christiane Bailey is a researcher in philosophy, coordinator of the Social Justice Centre at Concordia University in Montreal and is a member of the Groupe interuniversitaire de recherche en éthique environnementale et animale (Inter-university research group on environmental and animal ethics).

Axelle Playoust-Braure is a science journalist covering neglected issues related to animal farming and advocacy. She has a master’s degree in sociology and is a women’s rights activist, co-founder of the Collectif antispéciste pour la solidarité animale de Montréal (Montreal anti-speciesist collective for animal solidarity).

Photo Jo-Anne McArthur: Samantha Robinson with rescued sheep at Farm Sanctuary.

Notes:

- In his contribution to the book of Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella II, Terrorists or Freedom Fighters? Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, Lantern Books, 2004.

- This article by Christiane Bailey and Axelle Playoust-Braure is the translation of the French paper « Féminisme et cause animale » originally published in Ballast issue no. 5 (Autumn 2016). Translated by the Linguistic Pole of Projet Méduses.

- Emily Gaarder, Women and the Animal Rights Movement, Rutgers University Press, 2011.

- Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas, Mariner Books, 1963.

- Carol J. Adams, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, Bloomsbury, 2015.

- Or non-human animals.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1256b 20–25.

- Discourse that reasons, language as an instrument of reason.

- Aristotle, Politics, 1254 b 10-14 (translated by Benjamin Jowett).

- See the reviews by Je suis une pub spéciste on Facebook (www.facebook.com/jesuisunepubspeciste) and Tumblr (www.publispeciesism.tumblr.com).

- Ableism is the discrimination against individuals on the basis of their physical or intellectual abilities or disabilities.

- Frederick Douglass, Memoirs of a Slave, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Dover Publications, 1995.

- Paul Sollier, Guide pratique des maladies mentales, G. Masson, 1893, p. 363 – quoted by Christophe Traïni, La Cause animale – Essai de sociologie historique (1820-1980), PUF, 2011, p. 178.

- Craig Buettinger, “Antivivisection and the Charge of Zoophilia: Psychosis in the Early Twentieth Century”, The Historian 55(2), 1993, 277–288.

- Cf. Will Potter, Green is the New Red: An Insider’s Account of a Social Movement Under Siege, City Lights, 2011.

- Cf. 2016 Living Planet Index.

- Tony Weiss, The Ecological Hoofprint: The Global Burden of Industrial Livestock, Zed Books, 2013.

- FAO, World Livestock 2011 : Livestock in Food Security, 2011, p. 8 – Meat (excluding eggs and dairy) provides only 18% of protein and 8% of calories worldwide.

- FAO, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2014, p. 66.