This article reviews and popularizes a set of articles on the psychology of human-animal relations. In doing so, it shows the links between the marginalisation of animals and the marginalisation of humans by focusing on two issues: the animalistic dehumanisation of humans, and the perception of humans defending animals (or being perceived as doing so). It also criticizes and proposes possible ways of intervention.

Three main themes:

- the devaluation of animals and its role in the marginalization of animalized humans;

- the perception of vegetarians and animal advocates and the support for animal exploitation

- strategic considerations and possible interventions.

This article1 appears in Kristof Dhont & Gordon Hodson (Eds.) (2019). Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy. Abingdon: Routledge2.

* *

*

Abstract

The central premise of the present chapter is that humans routinely undervalue animals relative to themselves. This devaluing has implications not only for animals, in terms of welfare and exploitation, but also for humans. For instance, devaluing animals increases the social value of representing other social groups as animal-like, thus denying these human groups the protections otherwise afforded to humans (and one’s own group). But there are also implications for those who protect animals or, at minimum, refuse to engage in the exploitation of animals. Recent research demonstrates that among many meat eaters, vegans and vegetarians are relatively disliked and viewed as threatening. This is particularly the case for vegans and vegetarians who cite animal justice (vs health or environmental concerns) for their renunciation of meat. Overall the research record increasingly shows that our thinking about animals is intimately and systematically linked to our thinking about other human groups in ways that entrench dominance over animals and those mentally associated with animals. The implications of these associations are explored.

* *

*

My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment. My companion will be of the same nature as myself, and will be content with the same fare… the sun will shine on us as on man, and will ripen our food. The picture I present to you is peaceful and human, and you must feel that you could deny it only in the wantonness of power and cruelty.

Mary Shelley, 1818/2016, pp. 128–129

One could be forgiven for not recognizing the passage above as that from Dr. Frankenstein’s “monster,” a being created in a laboratory and comprised of both human and animal corpses3. In the 200 years since the publication of that book, this creature has arguably become one of the most reviled and hated villains of literature and film, gripping society with both fascination and horror. Of note, this monster was both made of animal parts (and thus uncivilized and not human) and was disinclined to eat or exploit animals4. As a non-human vegan, therefore, the monster is an intriguing character, being animal-like in composition while yearning for an enlightened existence that harms no animals (affording animals more rights than humans are generally willing to grant). Physically he is not human enough, yet mentally he is too human given his desperation to be accepted as human at all costs. The Frankenstein monster is thus an apt metaphor for the theme of this chapter, recognizing the complexity of our attitudes toward animals, animal-like humans, and humans who protect the rights of animals. Our central premise is that humans generally devalue animals and place a premium on the value of humans – except those deemed animal-like or who eschew the exploitation of animals – and that there are consequences of these valuation processes for animals and humans alike.

Devaluing animals relative to humans

Throughout history humans have generally placed themselves at the top of a hierarchy of animals (the so-called “Chain of Being,” see Brandt & Reyna, 2011)5. This conceptualization places a premium on humanity relative to all other species, allowing humans to feel entitled to use or exploit virtually any animal or land space for their survival or even mere pleasure. This premium is so omnipresent that any reader who is unconvinced by this point would be unlikely to become convinced by arguments or evidence we could raise here. But it is worth noting some of the more obvious examples that illustrate this point. Consider the notions of liberty and freedom: the vast majority of animals are denied personhood and the ensuing rights that are afforded to persons. Indeed, there exists fierce pushback against the notion of granting animals person status, even for animals widely considered “human-like” (e.g., chimpanzees) (Rosenblatt, 2017). In contrast, completely abstract and lifeless entities such as corporations are granted rights and personhood, enshrined by the US Supreme Court (Totenberg, 2014). Among objectors, granting some animals personhood would, it is feared, open the floodgates to include a multitude of other animals, robbing humans of their unique status and privilege. Such action would also take away the social value to be derived from representing human outgroups as animalistic and “lesser” (see Hodson, MacInnis, & Costello, 2014). To those with privilege and power, the devaluing of animals represents a central plank in a broader social structure that justifies the status quo and is thus deemed indispensable. Its removal could seriously jeopardize ideologies that justify inequality as an acceptable practice in the abstract.

Consider also the routine use of animals for research purposes. In the medical domain, much of this research is of such questionable value as to be considered mean-spirited. For example, Volkswagen was exposed for forcing monkeys to squat in cramped air-tight boxes while breathing car emissions for hours at a time (Connelly, 2018). Comparable procedures have been used by humans in committing extreme behaviors such as suicide or genocide (e.g., the Holocaust), yet are simply considered the cost of doing business when animals are the victims. Even worse, the majority of medical research studies on animals are ineffective at finding cures for human diseases (for an analysis on pharmaceutical testing see Kramer & Greek, 2018). These outdated methods of discovery are inefficient and slow to change given, in large part, the expendable nature of creatures that are so devalued relative to humans. Therefore, devaluing animals translates into harm not only for animals but for humans. Yet the public continues to assume that animal research aimed at curing human diseases is efficacious; the public would be much less supportive if they knew the true ineffectiveness of such research (Joffe, Bara, Anton, & Nobis, 2016). Without such knowledge, animal suffering for the benefit of humans to many is considered a cost of medicine; saving a human life at the cost of countless animal lives serves as its own justification. The devaluing of animals, and the premium afforded to humans, is so deeply engrained that essentially any potential benefit to humans is pursued at the cost of animal welfare and life.

Much closer to home we see ample evidence that, within the discipline of psychology, animals are regarded as lower beings than humans. Among the psychological community and related sciences, animals have been denied basic characteristics or qualities such as intelligence, personality, mind, and even pain perception (de Waal, 2009, 2016; Singer, 1975; Weiss, 2017). It should come as no surprise, therefore, that humans likened to animals have similarly been psychologically robbed of these characteristics in the minds of those seeking to rationalize the status quo and/or deny rights to these targets (e.g., Hodson et al., 2014), a topic we turn to next. In closing this present section, suffice it to say that there is considerable evidence that animals, relative to humans, are dramatically devalued by humans. Indeed, we are presently witnessing our planet’s so-called “Sixth Mass Extinction,” with human populations growing rapidly while levels of non-human species and lifeforms drop precipitously and dangerously (see Ceballos, Ehrlich, & Dirzo, 2017). To some extent these patterns reflect not only human dominance but our priorities. Thinking about animals as holding lesser value is unfortunately used to justify the mistreatment of animals and, as we next review, the mistreatment of human groups associated with animals.

Thinking about animals shapes thinking about “animal-like” humans

To this point we have focused on how humans tend to devalue animals relative to themselves. Next we seek to highlight some of our own research demonstrating how devaluing animals creates problems for people mentally represented as being animal-like, a phenomenon known as dehumanization. As a general process, dehumanization is operationalized as “the perception and/or belief that another person (or group) is relatively less human than the self (or ingroup)” (Hodson et al., 2014, p. 87, italics in original). Under this broader umbrella, there are different ways to dehumanize others, such as thinking of others as animal-like, as machine-like, as being devoid of “mind” and experience (see Haslam & Loughnan, 2014)6. In the present chapter we focus on animalistic dehumanization, a process whereby other humans are denied qualities that are generally deemed uniquely human and thus unrepresented in animals, or whereby humans are metaphorically likened to animals (see Loughnan, Haslam, & Kashima, 2009). Critically, this is a relative process, comparing the other to the self or one’s own group; it is rare for a human group to be entirely denied humanness. For example, prejudice-prone people oppose helping immigrants in need when such groups pose a supposed realistic (i.e., tangible) threat to the host nation. Such persons also oppose help to immigrants who supposedly pose symbolic (i.e., non-tangible) threats, such as speaking a different language or supporting a different religion – but in order to rationalize the rejection of a group not posing a realistic threat the group is also dehumanized (Costello & Hodson, 2011). Representing the other group as relatively less human facilitates the decision to offer them less help, because help is generally reserved for those most human.

Interspecies model of prejudice (IMP)

In thinking about or conceptualizing others as animal-like, and in particular to denigrate the “other” by doing so, necessarily draws a link between thinking about human outgroups and thinking about animals. In short, how we think about animals shapes our thinking about groups we consider animal-like. To put it simply, it would be no insult, or of no strategic social advantage, to label another human as animal-like if animals themselves were not devalued in the first place. The Interspecies Model of Prejudice (IMP; Hodson et al., 2014) proposes the following: greater perceived divide between humans and animals, that is, seeing animals as different from and inferior to humans, fuels the tendency to think about human outgroups as less human than our ingroup (the group to which we belong). In turn, this animalistic dehumanization of the outgroup fuels or facilitates a host of biases toward that group (e.g., prejudice, stereotypes, discrimination, failure to help). Put together, this process takes the following form: human-animal divide → outgroup animalistic dehumanization → outgroup biases. The implications of this model are considerable: human-human prejudices (e.g., racism) may find some of their origins in devaluing animals (i.e., the human-animal divide)7.

This proposal was first tested by Costello and Hodson (2010). In the first study, a sample of predominantly White Canadians self-reported: (a) the extent to which they perceived a human-animal divide; (b) the extent to which they considered immigrants less human than Canadians (using subtle measures whereby participants rated the extent to which each group is characterized by personality or emotional tendencies that have previously been shown to be considered particularly “human”); and (c) their attitudes toward immigrants. The IMP model was supported; the more participants distanced animals from humans, the greater their tendency to think about immigrants as relatively less human, which in turn predicted less favorable attitudes toward immigrants (see also Costello & Hodson, 2014a, 2014b). In a second study, participants’ perceptions of a human-animal divide were experimentally manipulated. More specifically, instead of measuring naturally occurring human-animal divide beliefs, participants were randomly assigned to read scientific-appearing articles on either the similarities or the differences between humans and animals. The rationale underpinning the study is that if one can reduce the human-animal divide perception, particularly in ways that “elevate” animals up to the level of humans, this should rob people of the ability or tendency to dehumanize a human outgroup. After all, when revaluing animals to put them on par with humans, there is little social value in then referring to the outgroup as animal-like; the “insult” has lost its sting. This prediction was supported – increasing the psychological value of animals reduced the animalistic dehumanization of immigrants, which in turn lessened prejudice toward that outgroup. Central to the theme of this chapter, therefore, interventions to change thinking about human-animal relations can have profound impact on human-human relations, opening up a whole new raft of potential prejudice interventions.

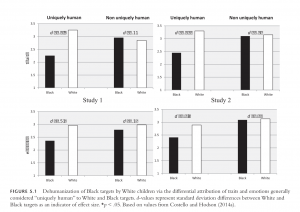

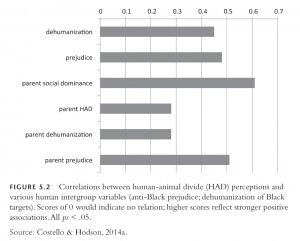

Presumably, these psychological linkages between humans and animals take root in the early formative years of development, and preliminary evidence supports this contention. Costello and Hodson (2014a) provided the first known demonstration that White children as young as 6-10 years animalistically dehumanize Black children. Using measures adapted from researchers assessing racial prejudices in children, Costello and Hodson asked these children to put cards, marked with words, into boxes that were fronted with a face of a White or Black child. These cards contained traits and emotions typically considered unique to humans (e.g., sympathy; embarrassment; open to experience) or shared with animals (e.g., happiness; fear; agreeable). Across both studies, young White children showed a striking tendency to attribute the more human qualities to White children, and to relatively deny such qualities to Black children (see Figure 5.1). Children, it appears, learn at an early age the social value in representing the outgroup as less human (and hence more animal-like). The children also employed a board that contained sliding images of animals and humans, both of which could be moved, allowing the children to express their perception of the human-animal divide. The more that these children considered animals as separate from and inferior to humans the more they dehumanized (and expressed negative attitudes toward) Black children (see Figure 5.2). Moreover, children seeing humans and animals as more different (vs. similar) also scored lower on a cognitive task relevant to thinking about the overlap between group categories generally. In children, therefore, more advanced cognitive abilities might be required to understand that targets that look different on the surface, such as humans and animals, may nonetheless be similar.

Interestingly, as shown in Figure 5.2, the more that children devalued animals, the more that their parents did the same, and the greater the parents’ racial prejudice and endorsement of inequality between human social groups (i.e., social dominance orientation, see Sidanius & Pratto, 1999; see also Dhont, Hodson, Leite, & Salmen, this volume). Such findings are consistent with the notion that how people think about animals as “lesser” than humans is associated with thinking that human outgroups are “lesser” than the purportedly more human ingroup, in ways that are systematic and even run in families. Intriguingly, new research shows that 5-10 year old White children also perceive that Black (vs. White) children experience less pain (Dore, Hoffman, Lillard, & Trawalter, 2018), in ways that are consistent with people believing that animals are less capable of pain (Singer, 1975). Such findings corroborate the assertion that thinking about animals is associated with thinking about others that are represented in animalistic terms.

Despite the IMP model showing support in university students, children, and adults, it is not intuitive to lay people that how we think about animals impacts how we think about (“animal-like”) others. In fact, there is evidence that people actively deny such associations. In a sample of undergraduates at a Canadian university, Costello and Hodson (2014b) asked people the extent to which a host of factors (e.g., closed-mindedness; negative intergroup contact; human-animal divide) were responsible for causing dehumanization and for causing ethnic prejudice. Factors such as closed-mindedness were considered strong causes, and others such as social identity and status were considered less responsible. But only 1 of the 15 potential causes was rated significantly lower than the mid-point on the scale, and thus indicated a denial of this factor as a cause of dehumanization or prejudice: human-animal divide. Likewise, when asked to rate solutions for solving dehumanization and ethnic prejudice, factors such as increasing intergroup contact and friendships were put forward as strong solutions, whereas others such as religion were rated as less helpful. But 2 of the 10 potential solutions were rated significantly lower than the scale midpoint, representing a denial that these factors could be solutions: highlighting animal-to-human similarity, and human-to-animal similarity. Nonetheless, in this same sample, those scoring higher in human-animal divide nonetheless expressed greater levels of outgroup dehumanization and outgroup prejudice. The link between human-animal relations and human-human relations appears to lie outside of everyday awareness, and worse, is actively denied as a cause of or solution to animalistic dehumanization of other groups and prejudices toward them. This may represent a simple and unmotivated denial (i.e., failure to recognize the relation), or it may represent a rationalization to justify not elevating the status of animals to solve human conflicts, or both. This represents fertile ground for future researchers.

We argue that the human-animal divide has implications for moral concern, not only for animals, but for humans. In a series of studies, Bastian, Costello, Loughnan, and Hodson (2012) pursued these implications using both Australian and Canadian samples. This research showed that those who naturally focus on human-animal similarities (instead of differences) include more animals in their circles of moral concern (i.e., consider a wider range of animals to be worthy of moral consideration). An experiment where participants were induced to think about the similarities of animals to humans or humans to animals further demonstrated that elevating animals “up” (as opposed to lowering humans “down”) boosts the number of animal species deemed worthy of moral concern. Consistent with the IMP model, a final study experimentally exposed participants to information that framed animals as similar to humans (or humans as similar to animals). The researchers observed not only a reduction in the willingness to exploit animals but an increase in the degree to which participants would take a moral stand to defend the unfair treatment of marginalized human groups in the host society (e.g., immigrants, Black people). Such findings again demonstrate the powerful links between thinking about animals and thinking about people; the links are so strong that experimentally inducing changes to how we think about animals brings along an accompanying positive change in how we think about groups that are often animalistically dehumanized.

Aversion to being considered animal-like

It is quite evident that people dehumanize other groups in the interest of maintaining or attaining group dominance or other benefits (for reviews see Haslam & Loughnan, 2014; Hodson et al., 2014). By extension, it is also important to look at how people feel and react when they are being (or believe to be) dehumanized by others, which has been called meta-dehumanization. Kteily, Hodson, and Bruneau (2016) investigated the presumably aversive reaction to meta-dehumanization among a variety of groups, for instance, by testing how Americans feel dehumanized by Arabs or Muslims, or how Israelis feel dehumanized by Palestinians. The researchers experimentally demonstrated that (falsely) informing people that another group dehumanizes the participant’s group resulted in dehumanization of that other group. Put simply, when we learn that others consider us animal-like, we retaliate or reciprocate, thinking of their group as animal-like. Across multiple studies, meta-dehumanization predicted negative outcomes for other groups, such as increased support by Americans for torturing Arabs or Muslims and the use of drone strikes against Muslim countries. Clearly, feeling dehumanized fuels dehumanization in turn that subsequently lowers the bar for negative behaviours toward that group. Ironically, therefore, being thought of as animals unleashes less civilized forms of conduct generally considered “beneath” civilized humans.

Fortunately, Kteily and colleagues (2016) also demonstrated that this process can be reversed and undone. That is, when we learn that others consider our group as particularly human and civilized, we in turn humanize that outgroup. Thus we not only feel negatively about being considered animal-like and retaliate by dehumanizing the other, but other groups are rewarded with the attribution of human qualities when they consider us as particularly good exemplars of being human.

Such interventions hold considerable promise, particularly given that contact with other groups is associated with less tendency to dehumanize the other group (Capozza, Falvo, di Bernardo, Vezzali, & Vistin, 2014), with contact itself being a powerful tool for reducing prejudices and bias (Hodson & Hewstone, 2013; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2011). The more that groups learn about each other, often via contact, on average they should view the outgroup in more humanizing terms, and feel in turn humanized by that group, at least in positive or neutral contact settings.

As we have seen, thinking about animals (e.g., their “distance” from humans) has implications for thinking about human outgroups that are animalized, as detailed in the IMP model. But we have also seen that thinking that others think that we are animal-like has implications for human outgroups, including increased dehumanization of that group and increased willingness to harm or injure that group. Collectively this demonstrates that people generally have a disdain of, and devaluation of, animals, and also dislike those considered to be animal-like (or the accusation of being so natured ourselves). This helps to put into perspective why Frankenstein’s monster, comprised of human and animal corpses and thus not fully human, has become one of the most recognized and reviled cultural icons of modern times. But what about the second part of the narrative concerning the disdain not only for animals and those deemed not fully human, but for those who advocate for animals (or at minimum avoid being complicit in animal exploitation)?

Negative reactions toward people who reject animal exploitation

Recently researchers have turned their attention toward reactions toward vegans and vegetarians. Generally, both vegetarians and meat-eaters consider vegetarians to be more “virtuous” albeit less masculine (Ruby & Heine, 2011). Interestingly, there can be negative implications for targets deemed virtuous or moral. For instance, Minson and Monin (2012) examined what they called “do-gooder derogation,” how people lash out at morally motivated others. Interestingly, they focused on how meat eaters feel about vegetarians, noting that by refraining from eating meat, vegetarians are seen by meat-eaters to publicly condemn meat consumption. This finding is pertinent to the meat paradox, whereby people generally wish no harm to animals but nonetheless harm and exploit animals through consumption (Loughnan, Bastian, & Haslam, 2014; see Piazza this volume). It is psychologically aversive to hold such contradictions in one’s mind, and the presence of vegetarians and vegans keeps to the fore of the mind that eating meat is a choice. In Study 1, Minson and Monin asked a sample of undergraduate meat eaters to freely list their thoughts associated with vegetarians. Despite (or presumably due to) seeing vegetarians as more moral than meat eaters, participants readily brought negative terms to mind (e.g., uptight; preachy). More importantly,the more morally superior participants believed vegetarians to consider themselves, the more negative were the descriptions of vegetarians by meat-eaters. In a follow-up experiment, undergraduate meat eaters indicated how they feel vegetarians view them personally, either before or after rating vegetarians along a series of dimensions. As expected, vegetarians were rated more negatively after (vs. before) thinking about how vegetarians view the participant (a meat eater). Thus, making salient that “do-gooder” vegetarians would supposedly look down on meat eaters for being less moral caused meat eaters to be more negative in their evaluations of vegetarians. The researchers suggest that thinking about vegetarians poses a threat to one’s sense of personal morality, inducing a backlash against vegetarians.

Subsequent research has considered some of the implications of considering non-meat eaters threatening. Intrigued by previous studies showing that right-wing (vs. left-wing) adherents are more likely to eat meat, we collected data among two community samples of meat eaters in Belgium (Dhont & Hodson, 2014). Participants completed two measures relevant to right-wing ideology: (a) social dominance orientation (SDO; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999), wherein higher scores reflect greater endorsement of intergroup inequality and hierarchy in group-life generally; and (b) right-wing authoritarianism (RWA; Altemeyer, 1996), wherein higher scores reflect greater conventionalism, respect for traditions, and aggression against norm violators. Political psychologists generally consider such measures to capture much of the left-right divide, with SDO pertaining to the acceptance of inequality on the right, and RWA pertaining to the resistance to change on the right (e.g., Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003). The main criteria of interest were participants’ meat consumption levels and their endorsement of animal exploitation more generally (e.g., using animals for testing cosmetics).

In both studies (Dhont & Hodson, 2014), those higher in SDO or RWA indeed consumed more meat and were more accepting of practices that exploit animals8. But in many ways, the real story concerns why this left-right divide exists. In each study participants also reported the extent to which they feel threatened by vegetarianism (e.g., eroding cultural traditions; damaging the economy), and the extent to which they as humans feel superiority (or entitlement) over animals. These two variables largely explained why right-wing adherents, relative to those on the left, eat more meat and endorse animal exploitation. And, in Study 2, these effects were found to be statistically independent from the extent to which participants found hedonic value in eating meat. In other words, right-leaning ideologies about how society should be structured (e.g., RWA, SDO) predict greater animal exploitation and meat consumption because these ideologies encourage beliefs that vegetarians (or vegans) are a cultural threat and that humans are superior and dominant over animals, independent of whether one even enjoys meat.

More recent evidence confirms the association between ideology on the one hand, and vegetarian threat and speciesism on the other. For instance, we collected data from Belgium, the UK, and the USA and found that those scoring higher in RWA, SDO, or political conservatism, hold greater beliefs that vegetarians pose a cultural threat, and endorsed greater speciesism (Dhont, Hodson, & Leite, 2016). These associations were quite strong, often in the r = .40 to .50 range, very large effects by contemporary standards in psychology (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016). Moreover, recent evidence highlights the importance of vegetarianism threat (i.e., regarding a human group) with regard to animal welfare. Researchers examined, in a 16-month longitudinal study, the extent to which vegetarianism threat and human supremacy predict subsequent moral exclusion of various animal types: food animals (e.g., cows, pigs), appealing wild animals (e.g., chimps, dolphins), unappealing wild animals (e.g., snakes, bats), and companion animals (e.g., cats, dogs) (Leite, Dhont, & Hodson, 2019). Of interest was the degree to which these US participants considered these animals to fall within their moral circles of concern (Laham, 2009; Opotow, 1990); animals that fall outside of one’s concern are generally considered fair game for being the brunt of indifference or exploitation. Leite and colleagues found that, even after controlling for initial moral concern regarding animals, beliefs about human supremacy and about vegetarianism threat predicted Time 2 moral exclusion of animal ratings. Specifically, those higher in human supremacy beliefs later demonstrated greater moral exclusion of all types of animals, whereas those higher in vegetarianism threat later demonstrated greater moral exclusion only of food animals (as predicted) and appealing wild animals. Thus beliefs about human supremacy over animals (i.e., human-animal), and about threats posed by vegetarians (i.e., human- human), both have real downstream consequences of the welfare of animals, here determining whether animals deserve moral protections.

Ideologies such as SDO and RWA, and ideologically-motivated beliefs such as human supremacy over animals and vegetarianism threat, are therefore powerful determinants of engaging in behaviors that are harmful to animals. Particularly intriguing is the finding that pushing back against vegetarians as a source of threat is a major factor underpinning practices that are harmful to animals (see Dhont & Hodson, 2014). And related findings confirm this general idea: In a community sample of Americans, variables such as SDO and RWA predicted the denial of climate change and resistance to taking action to curb its effects, in large part through pushback against environmentalists (Hoffarth & Hodson, 2016). Here we again see that viewing human outgroups (e.g., vegetarians; environmentalists) as threatening plays a role in promoting behaviors wherein human interests are put before those of animals and nature more generally. Thinking about animals and humans appears again intertwined.

But what about predicting prejudice toward vegetarians or vegans (henceforth veg*ns), in addition to feeling threat from such groups? Anecdotally, most veg*ns can recount many experiences of negativity and even discrimination. This encouraged Chin, Fisak, and Sims (2002) to develop the Attitudes Toward Vegetarians scale, tapping attitudes toward veg*n behaviours, beliefs, health/mental effects, and how to treat the group. A sample item reads: “Vegetarians preach too much about their beliefs and eating habits.” The authors found that those higher in authoritarianism (but not conservatism) expressed significantly more negative attitudes toward vegetarians. Contrary to their expectations however, scores overall reflected relatively positive attitudes. As the authors note, this might be attributable to the fact that the sample was a university sample (i.e., relatively liberal and young) and 81% female. Moreover, 84% knew a vegetarian personally, and indeed, many veg*ns may have been included in the analysis because the authors did not report dietary habits of respondents.

More recently MacInnis and Hodson (2017) examined the nature of anti-veg*n attitudes, and their consequences, more closely. Their first two samples were adult Americans (MTurk workers), with roughly equal numbers of men and women, and were all meat eaters. In these studies, attitudes were assessed with ratings thermometers (i.e., one’s feelings toward the group in question). In Study 1, both vegetarians and vegans were rated significantly more negatively than Black people, and equivalently to immigrants, asexuals, and atheists. Of the groups examined, only drug addicts were rated more negatively than vegetarians and vegans. There was little indication, however, of overall support for discriminatory policies in terms of hiring or renting an apartment to veg*ns. As expected, those higher in RWA, SDO, or conservatism were significantly more negative (and discriminatory) toward vegetarians or vegans. Moreover, and related to our earlier discussions of vegetarian threat, those on the right (vs. left) were more prejudiced and discriminatory because they considered vegetarians and vegans threatening.

Study 2 of MacInnis and Hodson (2017) found that meat eaters were biased against vegetarians and vegans depending on the reasons given for their dietary choice. Specifically, more negative attitudes were expressed toward those veg*n for animal rights reasons than for health or environmental reasons. Clearly veg*ns are more disliked when their food choices are based in morality, consistent with the view that vegetarians are “do-gooders” who highlight the moral imperfections in meat eaters (see Minson & Monin, 2012). In Study 1 of MacInnis and Hodson, male veg*ns were also significantly more disliked than their female counterparts, presumably due to their violation of masculinity norms, again highlighting that those avoiding meat are disliked for the specific nature of what they represent (and not merely as an “other” type of person).

And there is evidence that veg*ns feel the sting of stigma and discrimination. In Study 3 of MacInnis and Hodson (2017) the researchers actively recruited adult veg*ns through classified ads and social media groups dedicated to these groups. One quarter of vegans reported distancing from friends after disclosing being vegan, with 10% even observing such distancing by family members. A third of both vegans and vegetarians reported anxiety about revealing being veg*n to others, and understandably so: 46% of vegetarians, and 67% of vegans, reported some level of every-day discrimination in their lives. Not surprisingly, more than half of each group also reported engaging in coping strategies to cope with the discrimination and alienation. And consistent with the notion that threat reactions underlie some of the bias, vegans reported significantly more negative experiences than did vegetarians. Thus, the more a person rejects animal exploitation, the more they are rejected by meat-eaters; it is not simply the case that meat-eaters dislike veg*ns, but they dislike veg*ns the more they restrict or eliminate their animal consumption and use.

The studies of MacInnis and Hodson (2017) clearly demonstrate that veg*ns are disliked, as much if not more than, many of the other marginalized social groups (e.g., Blacks; immigrants). And this dislike is targeted and nuanced: vegans are disliked and rejected more than vegetarians; veg*n men are disliked more than their female counterparts; those who are veg*n for animal justice reasons are more disliked than those claiming environmental reasons or health reasons for their non-meat diets. Moreover, this negativity is psychologically experienced by veg*ns, as they report anxiety, discrimination, social distancing, and the need for coping mechanisms. Here again we witness pushback against those not eating meat, and the “moral threats” posed by veg*ns as they demonstrate that animal exploitation is not necessary or needed.

Recent research by Judge and Wilson (2019) supports many of the findings of MacInnis and Hodson (2017) but within a New Zealand context. In a large sample of more than 1300 citizens, they found that overall attitudes toward veg*ns were somewhat positive, that vegans were more disliked than vegetarians, and men (vs. women) show stronger biases against those not eating meat. They also confirmed that those scoring higher in RWA or SDO expressed more negative attitudes toward both vegans and vegetarians, as did those who consider the world dangerous or competitive. These findings nicely fit the central theme of this section of the chapter: those feeling rattled about the world in terms of instability and/or competition, and those more strongly endorsing right-leaning ideologies such as RWA and SDO, express consistently more negative attitudes toward vegans and vegetarians.

Another approach has been to consider the relation between one’s personal meat consumption and anti-veg*n bias. Would the amount of meat (e.g., beef) one consumes be related to the extent to which one distances from veg*ns? An ambitious study by Ruby and colleagues (2016) asked questions of relatively large numbers of people in four heavy beef-consuming nations: Argentina, Brazil, France, and the USA. Overall, men craved and consumed more beef than did women. Describing overall trends, the authors concluded that people generally show pro-beef attitudes across nations, with attitudes toward vegetarians being fairly neutral in valence. Using these rich data, Earle and Hodson (2017) conducted additional analyses to further determine whether a general pro-beef attitude, indicated by a stronger desire for and higher consumption and liking of beef, predicts general anti-vegetarian prejudice, indicated by feeling more bothered by, lesser admiration of, and lesser willingness to date vegetarians. This analysis revealed a very strong pattern: the more a person is pro-beef, the more negative their anti-vegetarian prejudice. Although statistically significant in all countries, the percentage of variance in anti-vegetarian prejudice explained by pro-beef orientations differed by country. Particularly remarkable is the finding that 43 percent of the variance in American anti-vegetarian attitudes was explained by personal pro-beef attitudes. Thus, meat-eaters who enjoy beef do not simply dislike vegetarians as a group, but the strength of their dislike is systematically and strongly linked to the degree that they personally enjoy beef. Such patterns are very consistent with the notion that meat-eaters pushback against non-meat eaters in light of the threat that such individuals pose to the meat-eater personally (and presumably morally).

If meat-eaters are more negative toward veg*ns as a function of how much meat they personally consume, this suggests sensitivity to personal choices and behaviors (e.g., guilt induction) that then becomes directed outward toward those disavowing meat consumption. This begs a related but distinct question: Might reminders that meat originates from animals impact attitudes toward veg*ns? A recent set of studies by Earle, Hodson, Dhont, and MacInnis (2019) addressed this question in an experimental context, exposing some participants to visual advertisements where animals were paired with meat (e.g., a lamb paired with a lamb chop) and others only to the meat image (e.g., a lamb chop). These images can be found at https://osf.io/25jfr. This manipulation exerted several interesting effects. Across studies, meat-animal reminders (vs. control) boosted empathy for the animal in question, and elevated distress about eating meat; in Study 2 it also boosted disgust at the thought of eating meat. Such reactions are widely known by the meat industry, who are generally careful to limit pairings of meat with animals to avoid putting off potential meat customers. But these psychological reactions, such as elevated empathy for animals paired with images of their meat “product”, exerted interesting knock-on effects, not only reducing participants’ willingness to eat meat, but also reducing biases against veg*ns. For instance, in Study 2, exposure to meat-animal reminders: (a) induced greater empathy for the meat-animal, which in turn lowered prejudice toward veg*ns; and (b) generated greater meat distress, which in turn lowered perceptions of veg*ns as culturally threatening. Thus, reminding meat-eaters that meat originates from living, sentient animals can reduce willingness to eat meat but also lower biases against those who refrain from eating meat.

In the title of their paper, MacInnis and Hodson (2017) expressed that “It ain’t easy eating greens.” This was not in reference to the difficulty in giving up meat and eating a plant-based diet, but rather reflect the marginalization by the meat-eating majority. We argue that better understanding anti-veg*n attitudes, and learning how to develop interventions, are key goals moving forward. Notably, veg*ns are disliked not for what they do, but for what they fail to do (and what those inactions represent). By failing to endorse mainstream ideologies and behaviors, these groups are targeted for failing to uphold the status quo and its legitimizing rationalizations (MacInnis & Hodson, 2017). In this way, veg*ns are not targeted because they eat the wrong forms of meat but because they disavow meat altogether, drawing attention to the meat paradox (i.e., that we care about animals but exploit them for food and other uses). And as our review has illustrated, vegetarians and vegans are considered a threat to society, against which the dominant meat culture pushes back strongly. We have also shown how such threats predict prejudices toward veg*ns, particularly among those with right-leaning ideologies and those who consume more meat. These findings support the assertion that people are threatened by their own pro-meat behaviors and beliefs that conflict with their positive self-image, who then lash out at others who highlight the moral shortcomings associated with eating meat.

Thinking about our relations with non-human animals

Anthony Bourdain, host of CNN’s Parts Unknown, was arguably one of America’s best-known food critics. He was not shy about his love of meat and his related disdain for veg*ns. We can let his words speak for themselves (“Vegans vs Anthony Bourdain?”, n.d.):

Vegetarians, and the Hezbollah-like splinter faction, the vegans, are a persistent irritant to any chef worth a damn… Vegetarians are the enemy of everything good and decent in the human spirit, an affront to all I stand for, the pure enjoyment of food.

The threat supposedly posed by veg*ns and the implications of a meat-free world is palpable, and mirror much of the revulsion expressed toward Frankenstein’s “monster,” a despised creature who seeks a vegan existence. As reflected in Bourdain’s words, contemporary interpretations of veg*ns as supposed “terrorists” and evil-doers serve a similar purpose: to vilify and alienate those who do not buy into and endorse a culture that considers the exploitation of animals as normal, natural, and necessary. Veg*ns may therefore be disliked, in part, because they “elevate” animals to human or near-human status, meaning that animals are given greater moral consideration. This can foster a backlash against veg*nism because the veg*n perspective not only makes people feel negatively for exploiting animals (who now would have moral consideration), but society loses a justification for violence toward and bias against groups deemed animal-like (also making society feel negatively).

Much of this would not have been lost on Mary Shelley who, along with her famous husband Percy, were part of the Romantic vegetarian movement (Adams, 2015) and keen to make a profound statement about human nature and social exclusion. Thus her deliberate depiction of the creature as the ultimate other by virtue of his animal origins and vegan ideals offered a biting commentary on society’s treatment of animals (and people). That we then feared the creature, and continue to do so 200 years later, is presumably a reflection of the undying human ambivalence about loving but exploiting animals. As noted by Cambridge professor Ottoline Leyser, such popular fiction often reflects society’s concerns of the day (Sample, 2017). For example, the Peter Parker character who subsequently became Spider-Man was originally bitten by a radioactive spider, with radioactivity a top concern at the time. But in later incarnations Parker was bitten by a genetically modified spider, at a time when concerns were being raised about genetically modified organisms. That the Frankenstein creature has remained the quintessential villain of popular culture for centuries presumably reflects society’s largely unchanged revulsion at both animal nature and the moral dilemmas faced by a species that supposedly loves yet exploits animals.

Implications

When we examine how we think about animals, animal-like humans, and humans who protect (or at minimum avoid exploiting) animals we recognize the complexity involved. We also recognize that much of this thinking is mired in rationalizations and ambivalent feelings. There are several implications of these findings. In terms of our scientific theories, the field needs to better recognize the links between human-animal relations and human-human relations. A related implication is that the field might need to move away from focusing so heavily on attitudes or evaluations of animals. Most people “like” animals but this seems disassociated from whether or not they will exploit or protect animals – the point at which the proverbial rubber hits the road. In the same way, most men “like” women but do little to fight for equal rights and pay for women. What matters most in predicting outcomes is not likely whether we like the other in question (e.g., animals; women; racial minorities), but rather our thoughts about their perceived value, and in particular, their exploitation value (see Hodson, 2017). That is, people endure the aversion induced by the meat paradox because the personal and cultural value they see in exploiting animals outweighs whether or not the target is likeable or whether such exploitation reflects poorly on one’s own moral character. Here again we see how rationalizations and dominance motives shape thinking about both humans and about animals. Consider how people will dehumanize other human groups, likening them to animals in ways that remove protections. The success of this process itself gains further social value and traction. Humans also engage in the “dehumanization” of animals (Hodson, 2017), as when Indians recently made moves to reclassify peacocks as vermin to justify their easier elimination as a nuisance. The more that another group or species is distanced from humans, either from humans to animal, or from animals to vermin, the less people show concern for that species and a willingness to engage protections.

There are also implications in terms of the development of bias interventions. In order for us to fully understand human-human prejudices, we must consider the overlap of these prejudices with speciesism and animal attitudes (Dhont et al., 2014, 2016), and that some human-human prejudices, especially those linked with animalistic dehumanization, find their roots in human-animal relations (Hodson et al., 2014; see also Dhont et al., this volume). This opens up tremendous potential for theorists and practitioners alike. Consider how reducing the human-animal divide lowers prejudice toward immigrants, even among those higher in SDO and generally anti-immigrant (Costello & Hodson, 2010). Interventions that target human-animal relations on the surface, but human-human relations underneath, might offer backdoor pathways to reducing conflict among human groups.

In keeping with the theme of the present book, there needs to be greater contact and connection between the researcher and theorist on the one hand, and the advocate on the other. Many researchers, particularly in psychology, have been exceptionally slow to recognize these human-animal connections and have much catching up to do. Much of what we have discussed in terms of research findings here has undoubtedly been long “known” but not empirically demonstrated by advocates: that animals are devalued relative to humans; that systems of inter-species oppression are linked under dominance motives. But changes are afoot in the science of psychology, as theorists and researchers have pushed the psychology of thinking about animals to the fore, with several recent publications on the psychology of speciesism and human-animal relations in top psychology journals (e.g., Amiot & Bastian, 2015; Caviola, Everett, & Faber, 2019). Psychologists entering the discussion bring with them the tools (empiricism) and the outlets (journals, conferences, classrooms) to shape thinking about animals in meaningful ways.

Despite these advances in our understanding about human-animal relations, there are limitations to the research conducted thus far. Although much of the literature we have discussed is experimental (e.g., Bastian et al., 2012; Costello & Hodson, 2010, 2011; Kteily et al., 2016), the evidence is often self-report in nature. Large-scale studies are needed with both behavioral and observational components. Longitudinal approaches (e.g., Leite et al., 2019) are also helpful in determining the flow of process over time. We are quick to defend self-report research as being extremely valuable, particularly when exploring the structural relations among constructs such as that between ethnic prejudice and speciesism (see Dhont et al., 2014, 2016). Complex questions about animals and human-animal relations will require a diverse range of methodologies.

Like most psychological research, the vast majority of the participants in these studies are considered WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic; see Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Although such people make up the vast majority of psychological research, they are atypical compared to the rest of the world. This point seems particularly poignant when it comes to human-animal relations, which are deeply rooted in local culture and tradition. A better understanding of how people think about animals and animal-like or animal-protecting others will only be possible when we expand the range of human groups considered and the range of animals of focus. Cross-cultural research is sorely needed in this discipline, and recent efforts have already proven fruitful (e.g., Ruby et al., 2016).

Take home message

Our closeness to animals is a source of considerable psychological angst, exacerbated when reminded how we routinely exploit and harm animals. Consider the ambivalence experienced when QueenVictoria observed her first orangutan in a public zoo. Despite being captivated by the creature she was nonetheless deeply disturbed, referring to the creature as “frightful and painfully and disagreeably human” (Lemonick & Dorfman, 2006). Relatedly, Desmond Morris relayed to Frans de Waal (2016) his experience working at the London Zoo, where apes had been trained to play in tea parties in front of visitors. The apes, however, were so adept at handling the basic tools (spoons, cups, teapots) that this disturbed the English public, who considered the act of taking tea as one that marks civilization. Incredibly, the apes were then retrained to throw food and mishandle the tools, which greatly relieved the public’s anxiety.

Such are the frailties of the human psyche. Humans go to considerable lengths to distinguish themselves from animals (e.g., de Waal, 2016; Hodson et al., 2014). In our quest for supremacy and self-overvaluing, we even seek to distance ourselves from other humans, and not simply those from other races. Lay people tend, for instance, to think of homo sapiens as virtually synonymous with “human,” despite there in fact being multiple subspecies of human: homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans. Interestingly, our supposed superiority within this highly select group is increasingly drawn into question. Recent discoveries of Palaeolithic art in Spain clearly demonstrate that Neanderthals were also capable of complex symbolic thought previously considered unique to homo sapiens (The Guardian, 2018). This comes after a barrage of evidence reveals that non-human animals are very much capable of intelligent thinking, moral behavior, and supposedly “human” emotions such as empathy (for reviews see de Waal, 2009, 2016). As such discoveries creep into the public consciousness, we anticipate a pushback that emphasizes the uniqueness of homo sapiens as distinct from other humans, as well as humans as distinct from other animals. After all, we are adept at moving the goal-posts to keep racial groups at a disadvantage, and we similarly move the goal-posts to distance ourselves from animals to give humans the advantage (de Waal, 2016). These psychological exercises that move the parameters in our favor all comes at a cost, it is worth remembering, to beings characterized as “the other.”

The take home message is that human psychology functions in ways that make life difficult for animals, people seen as more animal-like, and even for those not eating or otherwise exploiting animals. Relative to humans, animals are devalued, hold few rights, and are easy targets for exploitation as a result. Dehumanized humans suffer many of the same indignities. Moreover, veg*ns are a social minority who suffer prejudice, discrimination, and alienation, despite actively avoiding causing others harm objectively. Indeed, a perceived lack of social support is a strong predictor in explaining why people often lapse back to eating meat (Hodson & Earle, 2018). Addressing such issues will require societal change, and dare we say, enlightenment. Humans will need to scale back their exclusive dominance on the planet, even if only to save themselves. Animals will increasingly require strong legally-enforceable rights to protect them as they continue to be exploited and natural resources become more finite and land/sea becomes more compromised. An ideal starting point is to reduce or end the consumption of animals and shift to plant-based diets; a side benefit would be a dramatic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions that fuel climate change (Springman, Godfray, Rayner, & Scarborough, 2016). The meat paradox, a phenomenon rife with ambivalence, can become a useful tool in this endeavor instead of an obstacle. People already like animals, so harnessing this pre-existing positivity will be critical. Such actions will arguably become easier as veg*n populations continue to grow and new norms develop.

At the beginning of this chapter we contemplated whether Frankenstein’s monster is deemed too inhuman or too human. The answer, based on the research reviewed here, may lead us to the conclusion that he is both. Moreover, perhaps the real horror is that society recognizes itself in the monster – both too inhuman, as reflected in modern factory-farming practices, and too human, as reflected in our powerful ability to rationalize and justify our actions from our position of dominance and privilege.

Gordon Hodson, Kristof Dhont and Megan Earle

References

Adams, C. J. (2015). The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (25th anniversary edition). New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The Authoritarian Specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Amiot, C., & Bastian, B. (2015). Toward a psychology of human-animal relations, Psychological Bulletin, 141, 6–47. doi: 10.1037/a0038147

Bastian, B., Costello, K., Loughnan, S., & Hodson, G. (2012). When closing the human-animal divide expands moral concern: The importance of framing. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 421–429. doi: 10.1177/1948550611425106

Brandt, M. J., & Reyna, C. (2011). The chain of being: A hierarchy of morality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 428–446. doi:10.1177/1745691611414587

Capozza, D., Falvo, R., Di Bernardo, G. A., Vezzali, L., & Visintin, E. P. (2014). Intergroup contact as a strategy to improve humanness attributions: A review of studies. TPM: Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 21, 349–362. doi:10.4473/TPM21.3.9

Caviola, L., Everett, J. A. C., & Faber, N. S. (2019). The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(6), 1011–1029. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000182

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., & Dirzo, R. (2017). Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, E6089–E6096. https://pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1704949114

Chin, M. G., Fisak Jr., B., & Sims, V. K. (2002). Development of the Attitudes Toward Vegetarians Scale. Anthrozoos, 15, 332–342. doi: 10.2752/089279302786992441

Connelly, K. (2018). VW condemned for testing diesel fumes on humans and monkeys. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://theguardian.com/business/2018/jan/29/vw-condemned-for-testing-diesel-fumes-on-humans-and-monkeys

Costello, K., & Hodson, G. (2010). Exploring the roots of dehumanization: The role of animal-human similarity in promoting immigrant humanization. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13, 3–22. doi: 10.1177/1368430209347725

Costello, K., & Hodson, G. (2011). Social dominance-based threat reactions to immigrants in need of assistance. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 220–231. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.769 Costello, K., & Hodson, G. (2014a). Explaining dehumanization among children: The interspecies model of prejudice. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53, 175–197. doi:10.1111/bjso.12016

Costello, K., & Hodson, G. (2014b). Lay beliefs about the causes of and solutions to dehumanization and prejudice: Do non-experts recognize the role of human-animal relations?, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 278–288. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12221

de Waal, F. (2009). The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society. New York: Harmony Books.

de Waal, F. (2016). Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? New York: Norton.

Dhont, K., & Hodson, G. (2014). Why do right-wing adherents engage in more animal exploitation and meat consumption? Personality and Individual Differences, 64, 12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.002

Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Costello, K., & MacInnis, C. C. (2014). Social dominance orientation connects prejudicial human-human and human-animal relations. Personality and Individual Differences, 61–62, 105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.020

Dhont, K., Hodson, G., & Leite, A. C. (2016). Common ideological roots of speciesism and generalized ethnic prejudice: The social dominance human-animal relations model (SD-HARM). European Journal of Personality, 30, 507–522. doi: 10.1002/per.2069

Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Leite, A., & Salmen, A. (this volume). The psychology of speciesism. In K. Dhont & G. Hodson (Eds.) (2019), Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy. Abingdon: Routledge.

Dore, R. A., Hoffman, K. M., Lillard, A. S., & Trawalter, S. (2018). Developing cognitions about race: White 5- to 10-year-olds’ perceptions of hardship and pain. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 121–132. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2323

Earle, M., & Hodson, G. (2017). What’s your beef with vegetarians? Predicting anti-vegetarian prejudice from pro-beef attitudes across cultures. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.034

Earle, M., Hodson, G., Dhont, K., & MacInnis, C. C. (2019). Eating with our eyes (closed): Effects of visually associating animals with meat on anti-vegan/vegetarian attitudes and meat consumption willingness. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 22, 818–835. DOI: 10.1177/1368430219861848.

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

The Guardian. (2018). The Guardian view on Neanderthals. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/25/the-guardian-view-on-neanderthals-we-were-not-alone

Haslam, N., & Loughnan, S. (2014). Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A.(2010). The weirdest people in the world? (Target Article). Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Hodson, G. (2017). What is the pressing “animal question” about? Thinking/feeling capacity or exploitability? (Invited Commentary on Marino, 2017). Animal Sentience, 2(17), #12, pp. 1-4. Retrieved from http://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol2/ iss17/12/

Hodson, G., & Earle, M. (2018). Conservatism predicts lapses from vegetarian/vegan diets to meat consumption (through lower social justice concerns and social support). Appetite, 120, 75–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.08.027

Hodson, G., & Hewstone, M. (Eds.) (2013). Advances in Intergroup Contact. London: Psychology Press.

Hodson, G., MacInnis, C. C., & Costello, K. (2014). (Over)Valuing “humanness” as an aggravator of intergroup prejudices and discrimination. In P. G. Bain, J. Vaes, & J.-Ph. Leyens (Eds.), Humanness and Dehumanization (pp. 86–110). London: Psychology Press.

Hoffarth, M. R., & Hodson, G. (2016). Green on the outside, red on the inside: Perceived environmentalist threat as a factor explaining political polarization of climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.002

Joffe, A. R., Bara, M., Anton, N., & Nobis, N. (2016). The ethics of animal research: A survey of the public and scientists in North America. BMC Medical Ethics, 17, 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12910-016-0100-x

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375. doi: 10.1037/ 0033-2909.129.3.339

Judge, M., & Wilson, M. S. (2019). A dual-process model of attitudes toward vegetarians and vegans. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 169–178. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2386

Kramer, L. A., & Greek, R. (2018). Human stakeholders and the use of animals in drug development. Business and Society Review, 123, 3–58. doi: 10.1111/basr.12134

Kteily, N., Hodson, G., & Bruneau, E. (2016). They see us as less than human: Meta-dehumanization predicts intergroup conflict via reciprocal dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 343–370.

Laham, S. M. (2009). Expanding the moral circle: Inclusion and exclusion mindsets and circle of moral regard. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 250–253. doi: 10.1016/ j.jesp.2008.08.012

Leite, A. C., Dhont, K., & Hodson, G. (2019). Longitudinal effects of human supremacy beliefs and vegetarian threat on moral exclusion (vs. inclusion) of animals. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2497

Lemonick, M., & Dorfman, A. (2006). What makes us different? Time, 168, 44–53. Loughnan, S., Bastian, B., & Haslam, N. (2014). The psychology of eating animals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 32, 104–108. doi: 10.1177/0963721414525781

Loughnan, S., Haslam, N., & Kashima, Y. (2009). Understanding the relationship between attribute-based and metaphor-based dehumanization. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12, 747–762. doi: 10.1177/1368430209347726

MacInnis, C.C., & Hodson, G. (2017). It ain’t easy eating greens: Evidence of bias toward vegetarians and vegans from both source and target. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 20, 721–744. doi: 10.1177/1368430215618253

Minson, J. A., & Monin, B. (2012). Do-gooder derogation: Disparaging morally motivated minorities to defuse anticipated reproach. Social and Personality Psychological Science, 3, 200–207. doi: 10.1177/1948550611415695

Opotow, S. (1990). Moral exclusion and injustice. An introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 46, 1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540–4560.1990.tb00268.x

Pettigrew,T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2011). When Groups Meet: The Dynamics of Intergroup Contact, New York: Psychology Press.

Piazza, J. (this volume). Why people love animals yet continue to eat them. In K. Dhont & G. Hodson (Eds.) (2019), Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy. Abingdon: Routledge.

Rosenblatt, K. (2017). Do apes deserve “personhood” rights? Lawyer head to N.Y. supreme court to make case. NBC News. Retrieved from https://nbcnews.com/news/us-news/do-apes-deserve-personhood-rights-lawyer-heads-n-y-supreme-n731431

Ruby, M. B., Alvarenga, M. S., Rozin, P., Kirby, T. A., Richer, E., & Rutsztein, G. (2016). Attitudes toward beef and vegetarians in Argentina, Brazil, France, and the USA. Appetite, 96, 546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.10.018

Ruby, M. B., & Heine, S. J. (2011). Meat, morals, and masculinity. Appetite, 56, 447–450. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.018

Sample, I. (2017, Dec 27). Frankenpod 200: Celebrating Mary Shelley’s masterpiece – Science Weekly podcast. https://theguardian.com/science/audio/2017/dec/27/frankenstein-frankenpod-200-celebrating-mary-shelleys-masterpiece-science-weekly-podcast [see 30:40–31:45]

Sevillano, V., & Fiske, S. T. (this volume). Animals as social groups: An intergroup relations analysis of human-animal conflicts. In K. Dhont & G. Hodson (Eds.) (2019), Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy. Abingdon: Routledge.

Shelley, M. (1818/2016). Frankenstein. London: Collins Classics.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, P. (1975). Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals. New York: HarperCollins.

Springmann, M., Godfray, H. J., Rayner, M., & Scarborough, P. (2016). Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change co-benefits of dietary change. Proceedings of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States, 113, 4146–4151. doi:10.1073/ pnas.1523119113

Totenberg, N. (2014). When did companies become people? Excavating the legal evolution. NPR. Retrieved from https://npr.org/2014/07/28/335288388/when-did-companies- become-people-excavating-the-legal-evolution

Vegans vs. Anthony Bourdain? (n.d.) PETA. Retrieved from https://peta.org/living/food/vegans-vs-anthony-bourdain/

Weiss, A. (2017). Personality traits: A view from the animal kingdom. Journal of Personality, 86, 12–22. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12310

Notes:

- It was written by Gordon Hodson, Kristof Dhont and Megan Earle. The pdf of the article can be downloaded here.

- This unique book brings together research and theorizing on human-animal relations, animal advocacy, and the factors underlying exploitative attitudes and behaviors towards animals.

Why do we both love and exploit animals? Assembling some of the world’s leading academics and with insights and experiences gleaned from those on the front lines of animal advocacy, this pioneering collection breaks new ground, synthesizing scientific perspectives and empirical findings. The authors show the complexities and paradoxes in human-animal relations and reveal the factors shaping compassionate versus exploitative attitudes and behaviors towards animals. Exploring topical issues such as meat consumption, intensive farming, speciesism, and effective animal advocacy, this book demonstrates how we both value and devalue animals, how we can address animal suffering, and how our thinking about animals is connected to our thinking about human intergroup relations and the dehumanization of human groups.

This is essential reading for students, scholars, and professionals in the social and behavioral sciences interested in human-animal relations, and will also strongly appeal to members of animal rights organizations, animal rights advocates, policy makers, and charity workers. - We recognize that humans are animals; we use the term animals as a shorthand for non-human animals.

- Keen observers will note that Frankenstein’s monster craved and consumed milk and cheese (p. 92) and pushed a team of sled dogs at great speed (p. 185) when hunted angrily by his creator. But the monster’s philosophy and preferences were arguably vegan in nature. Indeed, prior to discovering and consuming these dairy products he nearly starved searching for acorns to eat. His vision for the world was one of social inclusion and existence without reliance on animal exploitation.

- For an alternative take that crosses this verticalValue dimension with a horizontal Threat Potential dimension (i.e., the ability to inflict harm), we refer the reader to Hodson and colleagues (2014). For a related discussion on how people rate animals in terms of their warmth versus competence, see Sevillano and Fiske (this volume).

- Fiske and colleagues also argue that people considered both low in warmth and competence as dehumanized, in light of their neuroscientific evidence such people are mentally processed as objects not people (see Sevillano & Fiske, this volume, for details).

- We also recognize that experimental manipulations of dehumanization might drive or influence human-animal divide perceptions. It is also possible that concepts such as dehumanization and divide perceptions are “downstream” consequences of hierarchical thinking (see Costello & Hodson, 2010, Study 1; for related points on dominance and hierarchy playing a more causal role, see Dhont, Hodson, Costello, & MacInnis, 2014; Dhont, Hodson, & Leite, 2016; Dhont, Hodson, Leite, & Salmen, this volume).

- On average the correlation between these ideology variables and meat consumption was approximately r = .33, a rather sizeable correlation, considered “large” in the individual differences field (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016). There are several ways of thinking about the meaning of this correlation. By one account, 11% (i.e., .33 x .33) of the variability in meat consumption was explained by SDO or RWA. Another way is to express it as a binomial effect size display: Among those above the median in SDO or RWA, approximately two-thirds were above the median in meat consumption.